Understanding the behavior of soil under various conditions stands as a fundamental requirement for any construction project. The science that governs how soil responds to loading, moisture changes, and environmental factors provides the foundation for safe infrastructure development. Whether designing a commercial building in Edmonton or planning a highway expansion project, engineers must account for the complex interactions between soil particles, water, and applied forces. This knowledge base ensures structures remain stable, foundations perform as designed, and project risks are properly mitigated throughout Alberta's diverse geological conditions.

The Fundamental Nature of Soil Behavior

Soil represents far more than simple dirt beneath our feet. As a three-phase material composed of solid particles, water, and air, it exhibits mechanical properties that change dramatically based on composition and environmental conditions. The solid particles themselves vary widely in size, from large gravels to microscopic clay minerals, each contributing unique characteristics to the overall soil mass.

Particle Size and Classification Systems

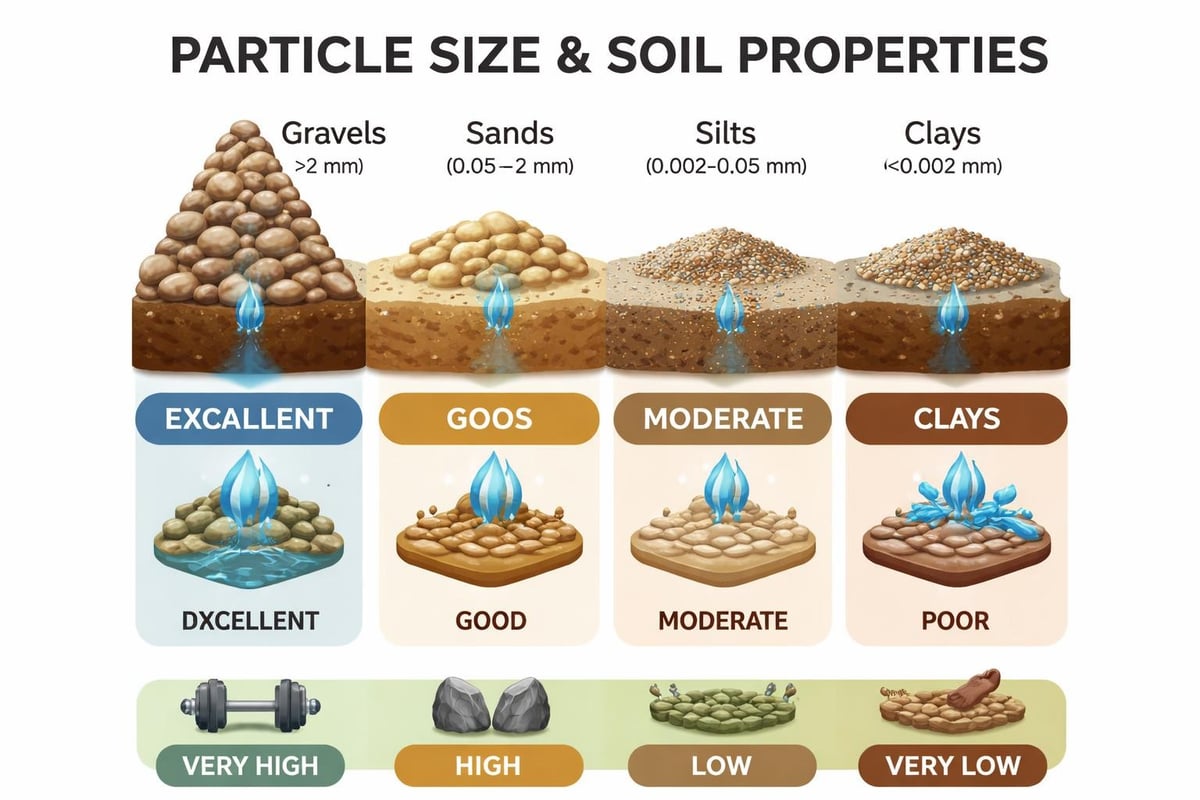

Engineers classify soils based on particle size distribution, which directly influences engineering properties. The classification system divides soils into distinct categories:

- Gravels: Particles larger than 4.75 mm that provide excellent drainage and high strength

- Sands: Particles between 0.075 mm and 4.75 mm offering good load-bearing capacity

- Silts: Fine particles between 0.002 mm and 0.075 mm with moderate plasticity

- Clays: Particles smaller than 0.002 mm exhibiting significant plasticity and cohesion

This classification framework guides engineers in predicting how soils will perform under various loading conditions. The practical applications of soil mechanics testing extend across all construction disciplines, from residential foundations to major infrastructure projects.

Stress Distribution and Effective Stress Principle

One of the most critical concepts involves understanding how stress distributes through soil masses. When loads apply to soil surfaces, stress propagates downward and outward in predictable patterns. However, soil mechanics recognizes that total stress comprises two components: effective stress carried by the soil skeleton and pore water pressure.

The effective stress principle, developed by Karl Terzaghi, revolutionized geotechnical engineering. This principle states that soil strength and deformation depend on effective stress rather than total stress. Water pressure within soil pores supports part of the applied load, reducing the stress transmitted through particle-to-particle contacts. Understanding this relationship proves essential for analyzing foundation settlement, slope stability, and soil stabilization and ground improvement strategies.

Testing Methods and Laboratory Analysis

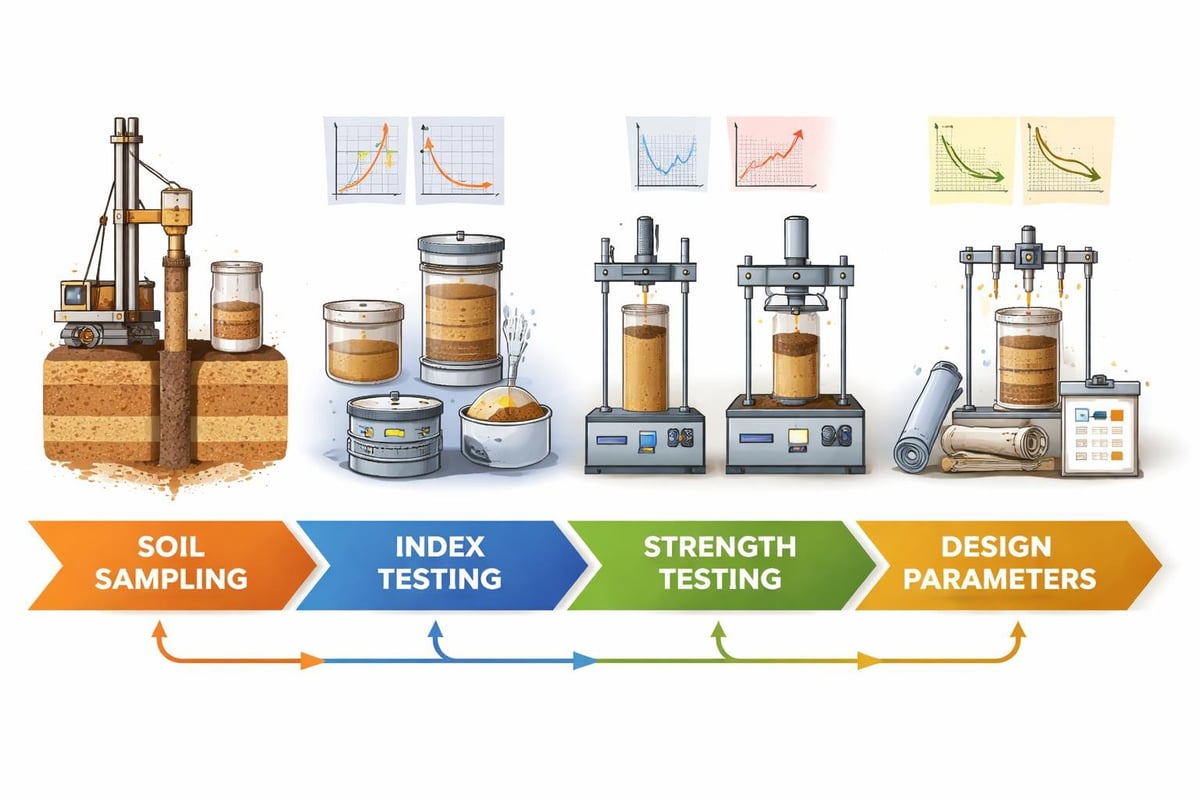

Accurate soil characterization requires systematic testing procedures that quantify engineering properties. Laboratories conduct various tests to determine parameters essential for design calculations and risk assessment.

Index Properties and Classification Tests

Initial soil assessment begins with index property determination. These tests establish baseline characteristics:

- Moisture content analysis measuring water present in soil samples

- Atterberg limits testing defining plasticity characteristics of fine-grained soils

- Grain size distribution through sieve analysis and hydrometer testing

- Specific gravity determination establishing particle density

- Organic content evaluation identifying potentially problematic materials

| Test Type | Primary Purpose | Typical Application |

|---|---|---|

| Moisture Content | Quantify water-to-solids ratio | All soil classifications |

| Liquid Limit | Define transition to liquid state | Clay and silt analysis |

| Plastic Limit | Establish lower plasticity bound | Fine-grained soil assessment |

| Gradation Analysis | Particle size distribution | Mix design and classification |

These fundamental tests provide data that engineers use to classify soils according to standardized systems like the Unified Soil Classification System (USCS).

Strength and Deformation Testing

Beyond classification, engineers must quantify how soils respond to applied loads. Advanced testing protocols measure strength parameters and deformation characteristics under controlled conditions.

Triaxial compression tests represent the gold standard for soil strength determination. These tests subject cylindrical specimens to confining pressure while applying axial loads, simulating field stress conditions. Results yield critical parameters including cohesion and internal friction angle, which govern soil shearing resistance.

Direct shear tests offer an alternative method, particularly useful for cohesionless soils like sands and gravels. The apparatus applies normal stress while forcing horizontal displacement, directly measuring shear strength along a predetermined failure plane.

Consolidation testing addresses time-dependent settlement behavior in saturated clays. As advanced modeling techniques in soil mechanics continue evolving, these laboratory results validate increasingly sophisticated predictive models. The one-dimensional consolidation test, or oedometer test, measures compression under incremental loads, providing data for settlement calculations and consolidation rate predictions.

Field Investigation and In-Situ Testing

While laboratory testing provides controlled conditions for property measurement, field investigations capture actual site conditions that influence project performance. Engineers employ various in-situ testing methods to complement laboratory work.

Standard Penetration Testing

The Standard Penetration Test (SPT) remains one of the most widely used field testing methods worldwide. Crews drive a split-spoon sampler into soil using a standardized hammer weight and drop height, counting the blows required to achieve specific penetration depths. The resulting N-value correlates with soil density, consistency, and approximate bearing capacity.

Alberta's varied geological conditions, from glacial tills to organic deposits, demand careful SPT interpretation. Engineers adjust raw N-values for factors including overburden pressure and equipment variables to obtain normalized values suitable for design calculations.

Cone Penetration Testing

Cone Penetration Testing (CPT) offers continuous soil profiling with minimal disturbance. The electronic cone penetrometer measures tip resistance, sleeve friction, and pore pressure as it advances through soil layers. This technology provides detailed subsurface characterization, particularly valuable for identifying thin weak layers that might escape detection through conventional boring programs.

The continuous data stream from CPT enables sophisticated soil behavior type classification and direct correlation with engineering parameters. Modern piezocone technology adds pore pressure measurement, enhancing analysis capabilities for saturated soils and determining consolidation characteristics.

Geophysical Methods

Non-invasive geophysical techniques complement traditional investigation methods. Seismic refraction surveys measure compression wave velocity through soil layers, identifying depth to bedrock and material stiffness variations. Electrical resistivity testing maps subsurface conditions based on conductivity differences between materials, proving particularly useful for limited subsurface investigation programs where extensive drilling proves impractical.

Applications in Foundation Engineering

The principles governing soil behavior translate directly into foundation design decisions that impact project safety and economy. Engineers apply soil mechanics concepts to select appropriate foundation types and predict long-term performance.

Shallow Foundation Design

Spread footings, continuous wall footings, and mat foundations transfer structural loads to near-surface soil layers. Design requires calculating bearing capacity, the maximum pressure soil can support without shear failure. Classical bearing capacity equations developed by Terzaghi, Meyerhof, and others incorporate soil strength parameters, foundation geometry, and embedment depth.

Settlement analysis complements bearing capacity calculations. Even when soil strength proves adequate, excessive settlement damages structures through differential movement and distortion. Engineers distinguish between immediate settlement occurring during construction and consolidation settlement developing over months or years in fine-grained soils.

| Foundation Type | Typical Depth | Suitable Soil Conditions | Primary Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Isolated Footings | 0.5-2 m | Dense sand, stiff clay | Economy for light loads |

| Strip Footings | 0.5-2 m | Uniform soil conditions | Continuous wall support |

| Mat Foundations | 1-3 m | Weak soils, heavy loads | Load distribution |

| Grade Beams | Varies | Variable soil conditions | Span weak zones |

Shallow foundation inspection services verify that constructed foundations meet design specifications and perform as anticipated.

Deep Foundation Systems

When near-surface soils lack adequate capacity, deep foundations transfer loads to stronger strata or develop capacity through friction along embedded surfaces. Driven piles, drilled shafts, and micropiles each suit specific soil conditions and loading requirements.

Pile capacity calculations consider both end-bearing resistance developed at the pile tip and skin friction mobilized along the shaft. The comprehensive theoretical and practical knowledge of soil mechanics informs these complex capacity predictions, accounting for installation effects, soil displacement, and load transfer mechanisms.

Slope Stability and Earth Retention

Natural and constructed slopes require careful analysis to prevent failure. Soil mechanics provides the analytical framework for evaluating stability under static and dynamic loading conditions.

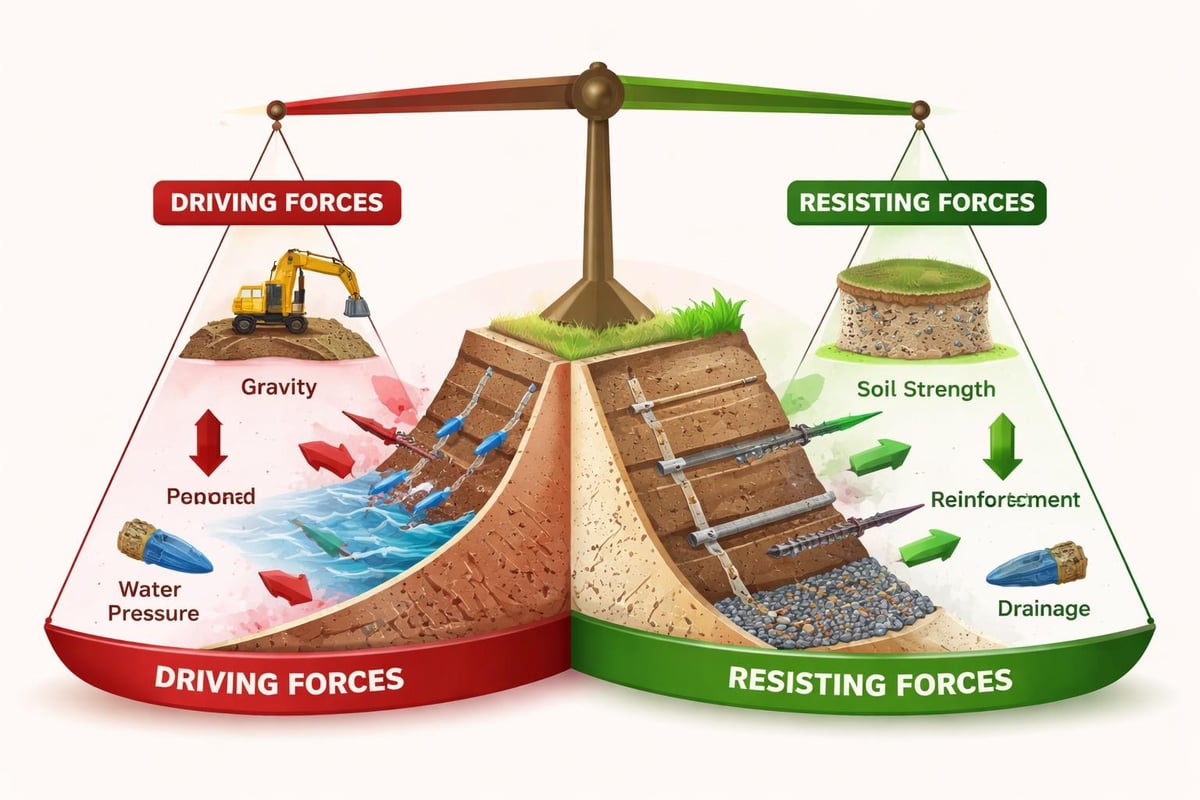

Limit Equilibrium Analysis

Traditional slope stability analysis employs limit equilibrium methods that compare driving forces promoting failure against resisting forces maintaining stability. The factor of safety quantifies this relationship, with values above 1.0 indicating stable conditions and values below 1.0 predicting failure.

Engineers evaluate potential failure surfaces using various methods:

- Ordinary Method of Slices for simple geometries and soil profiles

- Bishop's Simplified Method incorporating interslice forces for improved accuracy

- Spencer's Method for rigorous analysis satisfying all equilibrium conditions

- Morgenstern-Price Method handling complex geometries and pore pressure conditions

The principles of soil mechanics applied to slope stability analysis ensure safe designs for embankments, excavations, and natural hillsides.

Retaining Wall Design

Retaining structures must resist lateral earth pressures while maintaining stability against overturning, sliding, and bearing capacity failure. Lateral earth pressure magnitude depends on wall movement direction and magnitude, ranging from at-rest conditions through active and passive states.

Active earth pressure develops when walls move away from retained soil, allowing the soil mass to expand laterally. This represents the minimum pressure condition for design of most gravity walls and cantilever systems.

Passive earth pressure mobilizes when structures move into soil masses, compressing the soil and generating maximum resistance. Engineers rely on passive pressure for embedded wall stability and foundation resistance calculations.

Wall design must account for various factors:

- Soil strength parameters from laboratory testing

- Groundwater conditions and drainage provisions

- Surcharge loads from adjacent structures or traffic

- Seismic forces in earthquake-prone regions

- Construction sequencing and temporary stability

Soil Improvement and Ground Modification

When natural soil conditions prove inadequate for proposed construction, engineers implement ground improvement techniques to enhance engineering properties. These methods modify soil behavior through various mechanisms.

Mechanical Stabilization Methods

Compaction represents the most common improvement technique, increasing soil density through mechanical energy application. Vibratory rollers, impact compaction equipment, and dynamic compaction densify granular soils, improving strength and reducing compressibility.

For cohesive soils, preloading combined with vertical drains accelerates consolidation, removing water and increasing effective stress before construction. Wick drains or prefabricated vertical drains provide preferential drainage paths, reducing consolidation time from years to months.

Chemical Stabilization Approaches

Chemical admixtures alter soil properties through reactions with soil minerals or by filling void spaces. Common stabilization agents include:

- Portland cement creating cemented bonds between particles

- Lime reducing plasticity and improving workability of clays

- Fly ash providing pozzolanic reactions for long-term strength gain

- Chemical grouts filling voids and reducing permeability

Selection depends on soil type, project requirements, and environmental considerations. Successful stabilization requires understanding chemical reactions, mixing procedures, and curing requirements specific to each application.

Environmental Considerations and Sustainability

Modern geotechnical practice increasingly addresses environmental impacts and sustainability concerns. Engineers must consider how projects affect surrounding ecosystems and long-term resource management.

Contaminated Site Assessment

Industrial sites often contain soil contamination requiring specialized investigation and remediation. Geotechnical engineers work alongside environmental professionals to characterize contaminated soil extent, assess mobility potential, and design appropriate remediation strategies.

Contamination affects soil engineering properties, sometimes reducing strength or increasing compressibility. Projects involving contaminated sites require integrated assessment addressing both environmental compliance and geotechnical performance.

Sustainable Design Practices

Sustainability in geotechnical engineering involves several considerations:

- Minimizing soil excavation and offsite disposal

- Reusing on-site materials through stabilization when feasible

- Selecting foundation systems with reduced carbon footprints

- Considering life-cycle costs rather than initial construction expenses alone

- Designing for climate change impacts including precipitation pattern changes

These approaches reduce environmental impact while often providing economic benefits through material savings and construction efficiency gains.

Advanced Analysis and Numerical Modeling

Computer-based numerical analysis complements traditional analytical methods, enabling engineers to model complex geometries, non-linear behavior, and construction sequencing effects.

Finite Element Analysis

Finite element methods discretize soil masses into small elements, solving equilibrium equations at element boundaries to predict stress, strain, and displacement distributions. These tools handle complex problems including:

- Multi-layer soil profiles with varying properties

- Non-linear stress-strain relationships

- Staged construction sequences

- Soil-structure interaction effects

- Coupled flow and deformation analysis

Results provide detailed insights into project behavior, identifying potential issues before construction and optimizing designs for performance and economy.

Constitutive Model Selection

Accurate numerical analysis requires appropriate constitutive models representing soil behavior. Simple linear elastic models suit preliminary analyses, while advanced elastoplastic models capture yielding, hardening, and critical state behavior observed in real soils.

Model selection balances complexity against available material property data and project requirements. Over-sophisticated models lacking adequate calibration data may produce unreliable predictions despite computational rigor.

The principles and practices within this field form the foundation for safe, economical infrastructure development across diverse geological conditions. From laboratory testing and field investigation through design analysis and construction oversight, these engineering fundamentals guide decision-making at every project phase. When your project demands expert Geotechnical assessment and testing services backed by comprehensive knowledge of Alberta's unique soil conditions, ZALIG Consulting Ltd delivers the expertise and precision your team needs to move forward with confidence.