Foundation design represents one of the most critical aspects of structural engineering, forming the essential link between a structure and the ground beneath it. Every building, bridge, or infrastructure project relies on a properly engineered foundation to transfer loads safely to the soil while maintaining stability throughout the structure's lifespan. The complexity of this design process requires careful consideration of multiple factors, including soil properties, environmental conditions, structural loads, and local building codes.

Understanding Foundation Design Fundamentals

The process of foundation design begins with recognizing that no two sites are identical. Each location presents unique geological characteristics, groundwater conditions, and environmental factors that directly influence the selection and configuration of foundation systems. Engineers must balance technical requirements with economic constraints while ensuring safety and long-term performance.

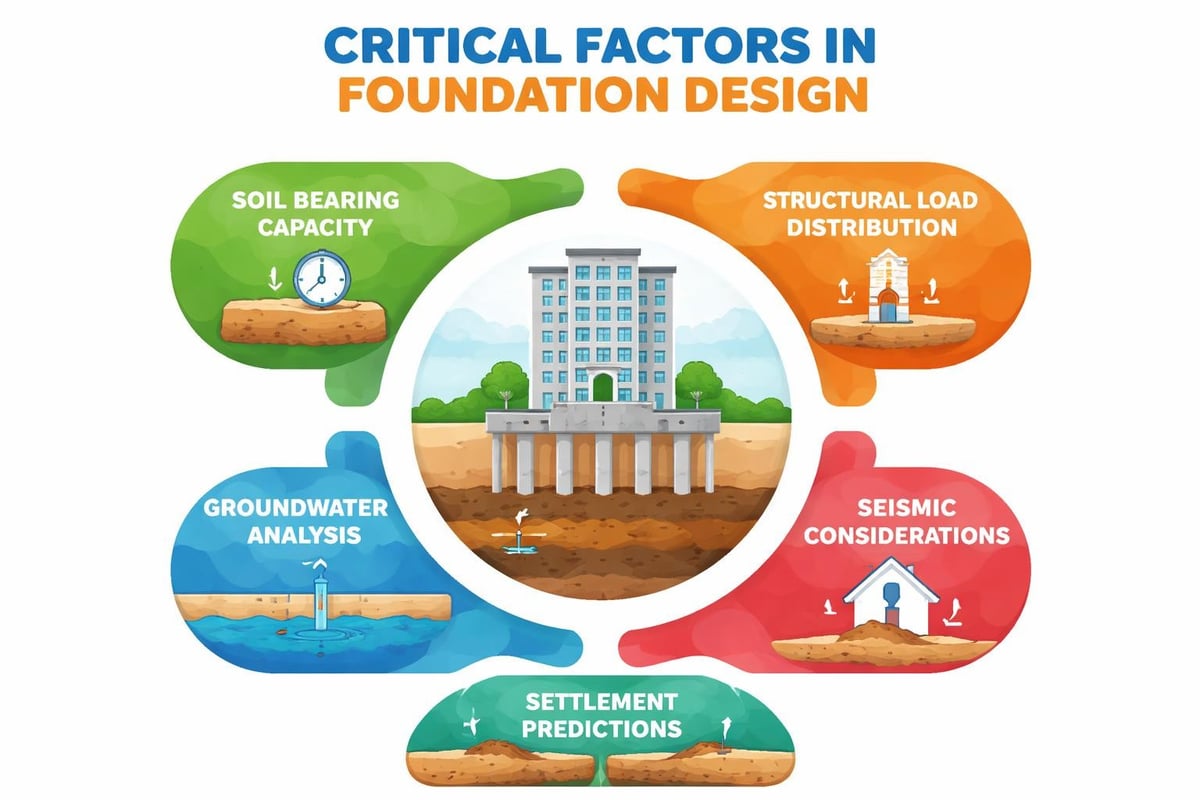

Key considerations in foundation design include:

- Soil bearing capacity and compressibility characteristics

- Anticipated structural loads and their distribution patterns

- Groundwater levels and seasonal fluctuations

- Local seismic activity and environmental conditions

- Construction feasibility and budget parameters

- Long-term settlement predictions and differential movement

The foundation serves multiple essential functions beyond simply supporting the structure above. It distributes concentrated loads across a wider area, prevents excessive settlement, resists lateral forces from wind or seismic events, and protects against frost heave or expansive soil movements.

Soil Investigation and Site Analysis

Comprehensive geotechnical investigation forms the cornerstone of successful foundation design. Without accurate subsurface information, engineers cannot make informed decisions about foundation type, depth, or configuration. Professional Geotechnical services provide essential data through soil borings, laboratory testing, and field investigations that reveal the ground conditions underlying a project site.

The investigation process typically involves multiple soil borings at strategic locations across the site. These borings extract samples for laboratory analysis, measuring properties such as moisture content, density, shear strength, and consolidation characteristics. Standard Penetration Tests (SPT) conducted during drilling provide valuable resistance measurements that correlate with soil strength and consistency.

Laboratory testing extends the field investigation by quantifying specific soil parameters under controlled conditions. Engineers evaluate grain size distribution, plasticity indices, permeability coefficients, and consolidation behavior. Permeability testing reveals how water moves through soil layers, critical information for foundation drainage design and groundwater management strategies.

Foundation Types and Selection Criteria

Engineers select foundation systems based on a comprehensive evaluation of site conditions, structural requirements, and project constraints. The decision matrix weighs numerous factors simultaneously, as outlined in the Foundation Guide, which categorizes various foundation systems according to their applications and performance characteristics.

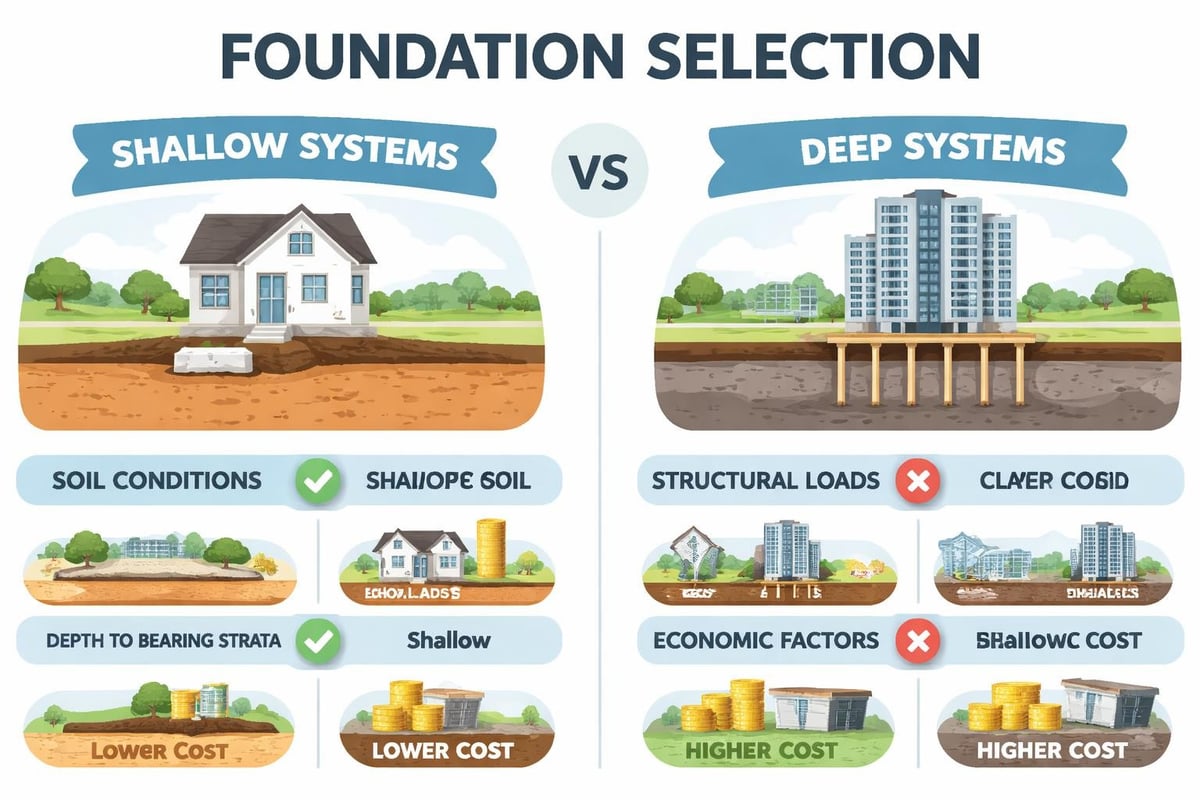

Shallow Foundation Systems

Shallow foundations transfer loads to near-surface soil layers when competent bearing strata exist within reasonable depths. These economical solutions work effectively in favorable soil conditions where bearing capacity exceeds structural demands with adequate safety margins.

| Foundation Type | Typical Applications | Bearing Depth Range | Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spread Footings | Columns, concentrated loads | 3-6 feet | Cost-effective, simple construction |

| Strip Footings | Bearing walls, continuous loads | 2-5 feet | Uniform load distribution |

| Mat Foundations | Large buildings, weak soils | 4-8 feet | Reduces differential settlement |

| Combined Footings | Adjacent columns, property lines | 3-7 feet | Space-efficient design |

Spread footings represent the most common shallow foundation type, enlarging the base area beneath columns or walls to reduce bearing pressure on underlying soil. Engineers size these footings by calculating the required area that keeps soil pressure below allowable limits while accounting for safety factors. The Texas Society of Civil Engineers provides detailed guidelines for residential foundation evaluation and design that illustrate these principles.

Strip footings support continuous bearing walls, distributing loads linearly along the wall length. These foundations prove particularly effective for load-bearing wall construction and maintain consistent bearing pressures across their length. Design calculations verify that maximum soil pressures remain within safe limits while providing adequate structural thickness to resist bending moments.

Deep Foundation Applications

Deep foundations become necessary when surface soils lack sufficient bearing capacity or when structures must resist significant lateral forces or uplift. These systems transfer loads through weak surface layers to competent strata at greater depths or develop capacity through skin friction along their length.

Pile foundations offer distinct advantages:

- Transfer loads through weak soil to bedrock or dense layers

- Resist uplift forces in tension applications

- Provide lateral stability against horizontal loads

- Minimize settlement in compressible soil conditions

- Enable construction over water or unstable ground

Driven piles use impact hammers to force prefabricated elements into the ground, displacing soil and densifying surrounding material. Engineers specify steel H-piles, concrete piles, or timber piles based on load requirements, soil conditions, and environmental considerations. The driving process creates vibrations and noise that may restrict use in sensitive urban areas.

Drilled shafts or caissons involve excavating cylindrical holes, placing reinforcement cages, and filling with concrete. This method minimizes vibration concerns while allowing larger diameters and capacities than typical piles. Inspection of excavated holes verifies soil conditions match design assumptions before concrete placement.

Load Analysis and Structural Calculations

Accurate load determination drives every aspect of foundation design. Engineers must quantify all forces acting on the foundation, including dead loads from the structure's weight, live loads from occupancy or equipment, and environmental loads from wind, snow, or seismic events. The Texas Department of Transportation Bridge Design Manual outlines comprehensive requirements for designing bridge foundations that account for these complex loading scenarios.

Dead and Live Load Calculations

Dead loads represent permanent gravity forces from structural elements, finishes, and fixed equipment. Designers calculate these loads by multiplying material volumes by unit weights, summing contributions from floors, walls, roofs, and architectural components. Accuracy matters because these loads remain constant throughout the structure's life.

Live loads vary based on building occupancy and use patterns. Building codes specify minimum live load values for different occupancies, from residential spaces requiring 40 pounds per square foot to assembly areas demanding 100 pounds per square foot or more. Reduction factors may apply for large tributary areas where simultaneous maximum loading proves unlikely.

- Calculate total dead load from structural drawings and specifications

- Determine applicable live loads from building code requirements

- Apply appropriate load combinations per structural standards

- Factor loads according to limit state design methodology

- Distribute loads to individual foundation elements

- Verify foundation capacity exceeds factored demand with adequate safety

Bearing Capacity Analysis

Foundation design requires calculating the ultimate bearing capacity of underlying soil and applying appropriate safety factors to establish allowable bearing pressures. The bearing capacity equation accounts for soil cohesion, internal friction angle, overburden pressure, and foundation geometry through empirically derived bearing capacity factors.

Engineers verify that applied loads create soil pressures below the allowable bearing capacity while also checking settlement predictions. Even when bearing capacity proves adequate, excessive settlement or differential movement between foundation elements can damage structures. Consolidation analysis predicts long-term settlement in clay soils, while immediate settlement calculations address elastic compression in granular materials.

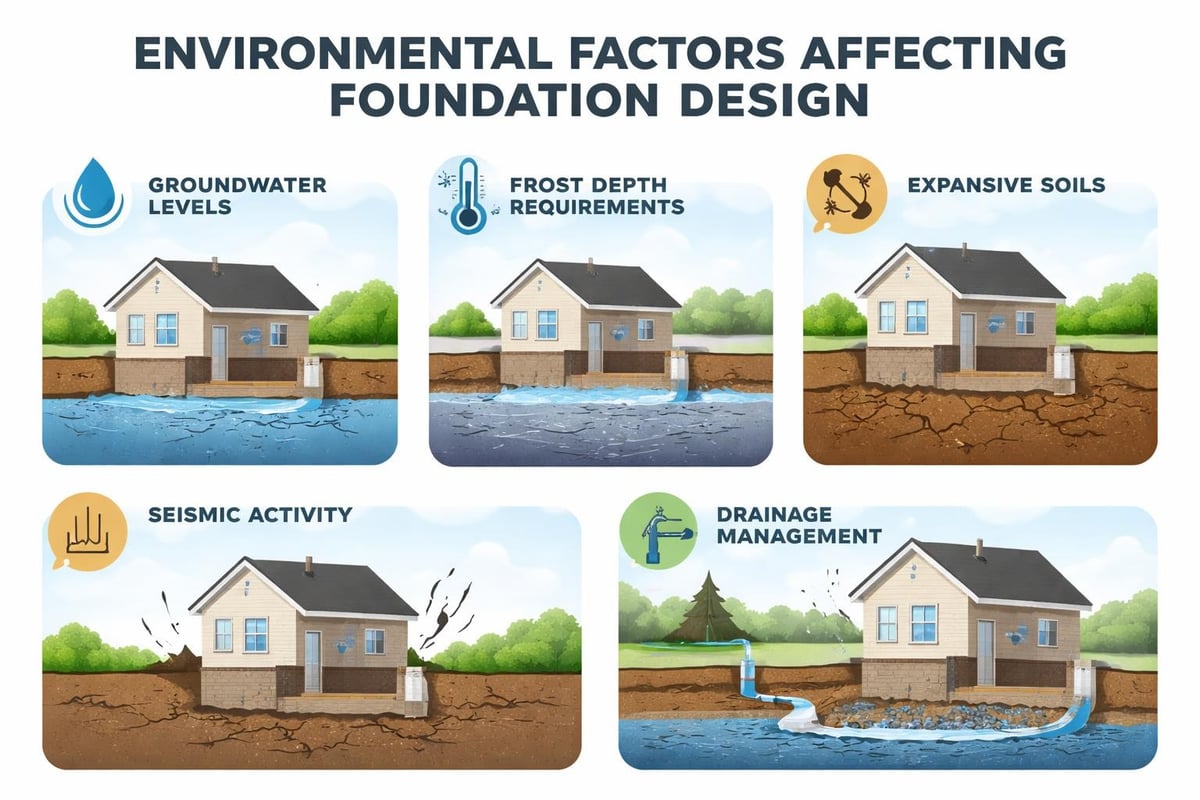

Environmental and Site-Specific Considerations

Foundation design extends beyond simple structural calculations to encompass environmental factors that affect long-term performance. Groundwater conditions influence both construction methodology and permanent foundation behavior. High water tables may require dewatering during construction, waterproofing measures, or specialized foundation systems that resist buoyancy forces.

Frost Depth and Seasonal Effects

In cold climates, foundations must extend below frost depth to prevent heaving damage when moisture in soil freezes and expands. Alberta's climate presents particular challenges where frost penetration reaches significant depths during winter months. Building codes specify minimum foundation depths based on regional frost data, though site-specific factors like soil type, drainage, and vegetation affect actual frost penetration.

Expansive soils containing clay minerals swell when absorbing moisture and shrink during dry periods. This volumetric change exerts substantial pressures on foundations and can cause severe distress if not properly addressed. Design strategies include deepening foundations below the active zone, using post-tensioned slabs to resist movement, or removing and replacing expansive material with engineered fill.

Mitigation strategies for problematic soil conditions:

- Chemical stabilization with lime or cement

- Moisture control through proper drainage systems

- Structural systems designed to accommodate movement

- Deep foundations extending through active zones

- Engineered fill replacement in critical areas

The NYC Department of Buildings emphasizes the importance of proper shoring and underpinning design when working adjacent to existing foundations, highlighting safety considerations that apply across different jurisdictions.

Design Standards and Code Compliance

Foundation design must comply with applicable building codes and engineering standards that establish minimum safety requirements. These regulations incorporate decades of engineering experience and research into prescriptive requirements and performance criteria. Autodesk’s foundation design guidelines reference various international geotechnical codes that provide comprehensive design rules for different foundation types.

Load and Resistance Factor Design

Modern foundation design typically employs Load and Resistance Factor Design (LRFD) methodology, which applies different factors to loads and material resistances based on their variability and uncertainty. This probabilistic approach provides more consistent reliability across different design scenarios compared to older allowable stress methods.

LRFD factors increase applied loads while reducing material strengths, ensuring adequate safety margins account for construction variability, material inconsistencies, and loading uncertainties. The resulting foundation dimensions must satisfy both strength requirements and serviceability criteria limiting deflections and settlements.

Construction Considerations and Quality Control

Successful foundation performance depends equally on proper design and quality construction practices. Even the most sophisticated engineering becomes ineffective if construction deviates from design intent or encounters unexpected conditions. Construction monitoring and materials testing verify that installed foundations match design specifications.

| Quality Control Element | Testing/Verification Method | Typical Frequency |

|---|---|---|

| Concrete strength | Cylinder compression tests | Per pour batch |

| Reinforcement placement | Visual inspection, cover measurement | Continuous |

| Excavation depth/condition | Survey verification, soil classification | Each foundation |

| Bearing surface preparation | Visual inspection, density testing | Before concrete placement |

| Pile driving resistance | Dynamic monitoring, load testing | Per specification |

Unexpected soil conditions discovered during excavation may require design modifications. Engineers should remain available during construction to evaluate unforeseen circumstances and provide timely solutions. Documentation of as-built conditions creates valuable records for future reference and any necessary structural modifications.

Professional materials testing ensures concrete quality meets design specifications. Slump tests verify workability before placement, while compressive strength testing of cured cylinders confirms adequate strength development. Testing frequency follows code requirements and project specifications, with increased sampling for critical structural elements.

Advanced Foundation Design Techniques

Complex projects may require sophisticated analysis methods beyond conventional design approaches. Finite element analysis models soil-structure interaction, predicting foundation behavior under various loading scenarios with greater accuracy than simplified hand calculations. These computational tools prove valuable for unusual geometries, challenging soil conditions, or structures with stringent performance requirements.

Geotechnical Instrumentation and Monitoring

Instrumentation programs monitor foundation performance during and after construction, validating design assumptions and providing early warning of unexpected behavior. Settlement monitoring surveys track vertical movement over time, comparing actual performance against predictions. Inclinometers measure lateral movement in deep foundations or retaining systems, while piezometers monitor groundwater pressures affecting foundation stability.

This monitoring approach proves particularly valuable for projects on marginal sites or innovative foundation systems where field performance data enhances understanding beyond theoretical predictions. Engineers can adjust construction procedures or implement corrective measures if monitoring reveals conditions deviating from design expectations.

Understanding slope stability becomes critical when foundations must be constructed on or near sloping terrain. The interaction between foundation loads and slope geometry requires careful analysis to prevent failure mechanisms that could undermine structural support. Design approaches may include terracing, retaining systems, or deep foundations extending to stable strata below potential slip surfaces.

Foundation design requires comprehensive integration of geotechnical investigation, structural analysis, environmental assessment, and construction expertise to develop safe and economical solutions. The principles outlined here apply across residential, commercial, and infrastructure projects, though specific applications vary with project scale and complexity. Whether you're planning a new development, evaluating existing structures, or addressing foundation distress, professional engineering guidance ensures proper design and implementation. ZALIG Consulting Ltd brings extensive geotechnical and materials testing experience to foundation projects throughout Alberta, providing the technical expertise and local knowledge necessary for successful outcomes from initial site investigation through construction completion.